CULTURE

© Chill Shine

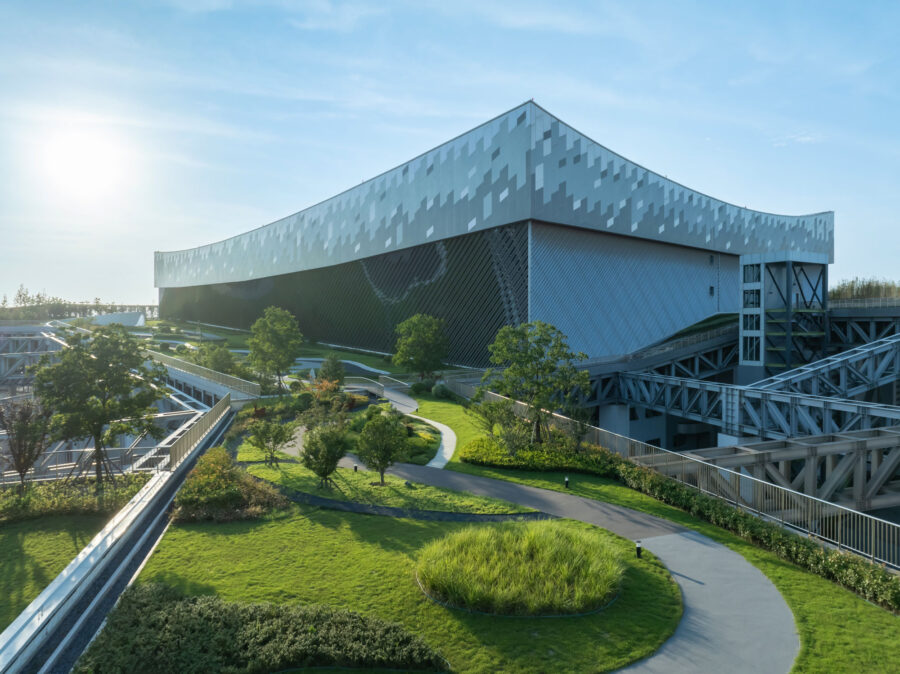

〈怒江七十二道拐展望台(Nujiang River 72 Canyon Scenic Area)〉は、中国の四川からチベットへ向かう道中で、「悪魔の区間」と称される最もスリリングな場所に建設された、川に飛び出すガラス床の展望台や川を跨ぐガラスの吊り橋からなる場所です。

成都を拠点に活動する建築事務所 Archermit が設計しました。

注目ポイント

- チベットへの「挑戦」の精神を体現する建築コンセプト

- 130m超の断崖に37m突き出す、ヘアピンカーブから着想したガラス展望台

- 車での通行時にも揺れる旧怒江大橋を参照したガラス吊橋

- この地に道路を建設したという偉業を身をもって感じる体験装置として設計

(以下、Archermitから提供されたプレスキットのテキストの抄訳)

© Archermit

© Chill Shine

「身体で測る」怒江の危険

チベットを夢見る子供たちは、誰もがG318国道の夢を抱いている。「中国の風景の道」と称される四川チベット公路は、旅人にとって常に聖なるルートであった。成都からラサへ向かう道程の南北分岐点を200km余り過ぎた地点に、この旅で最も壮観な区間がある。

チベット語で「勇士の山麓の村」を意味するバソイ(Baxoi)の小さな町には、バンダ草原、怒江大峡谷、然烏湖、来古氷河といった名所が点在し、G318沿いに真珠のように連なっている。中でも旅人が最も期待する挑戦は、バソイ内に位置し「悪魔の区間」とも称される怒江七十二道拐である。

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

チベットに挑む「挑戦」の精神を体現する展望台

「天に目を向け、地獄に身を置く」という言葉は、多くのチベット訪問者の実感を表している。それでもチベットは今なお精神的な目的地であり続ける。

文化的信念であれ、風景や風習であれ、「体験」こそがあらゆるタイプの旅行者がチベットを訪れる核心的な動機である。五体投地の巡礼であれ、トレッキング、サイクリング、自家用車での旅であれ、自己挑戦こそが多くのチベット愛好家の核心的な信念と追求である。

© Chill Shine

© Arch-exist

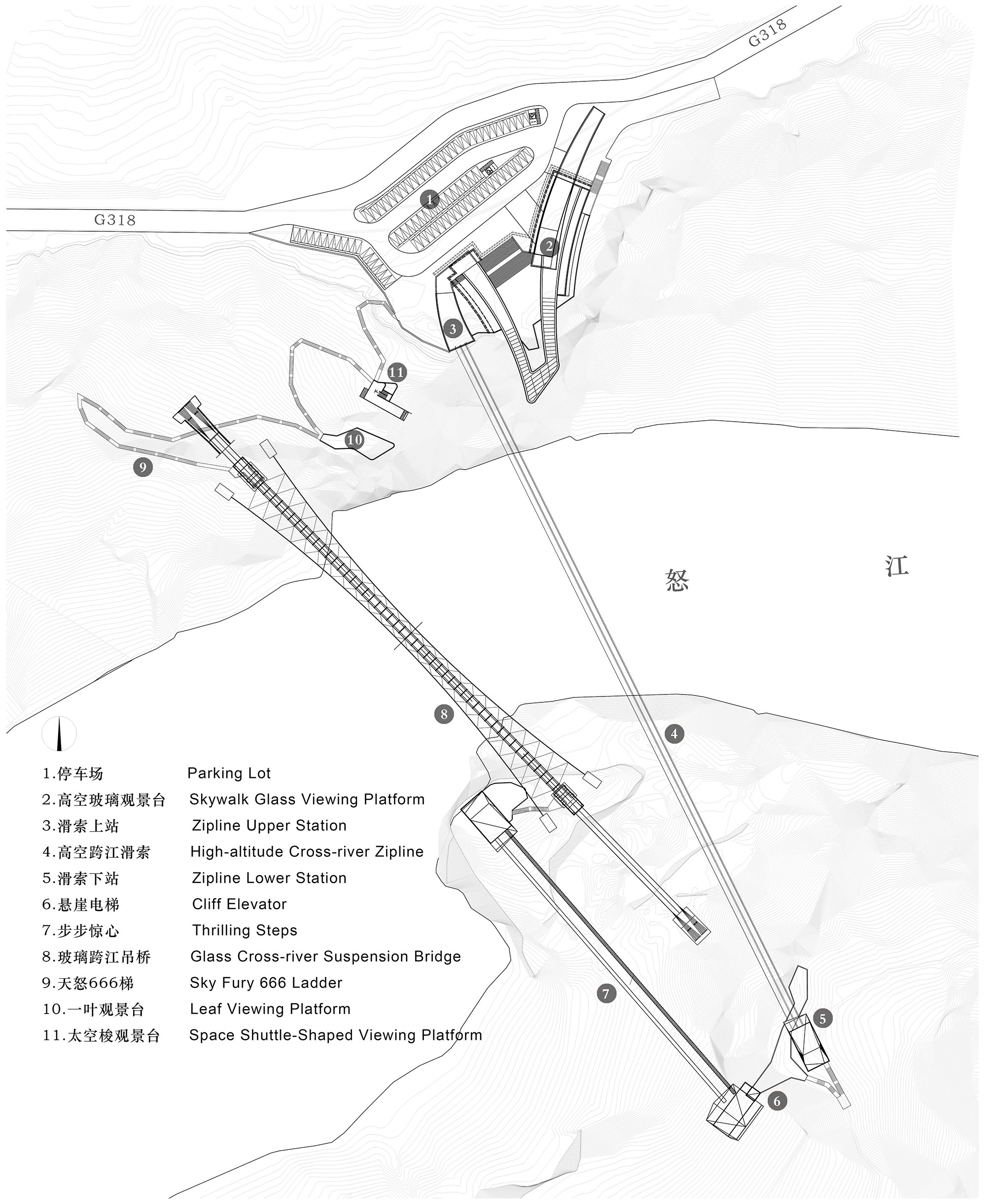

〈怒江七十二道拐展望台〉はチベット自治区昌都市巴竹県布則村に位置し、巴竹県から約48.5km、昌都邦達空港から約97kmにあり、G318で最も危険な区間である。

設計・建設・観光体験のすべては「挑戦」の精神を体現し、四川チベット公路の偉業に敬意を示している。すべてのインスピレーションは、この神秘的な景観道路から得た。

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

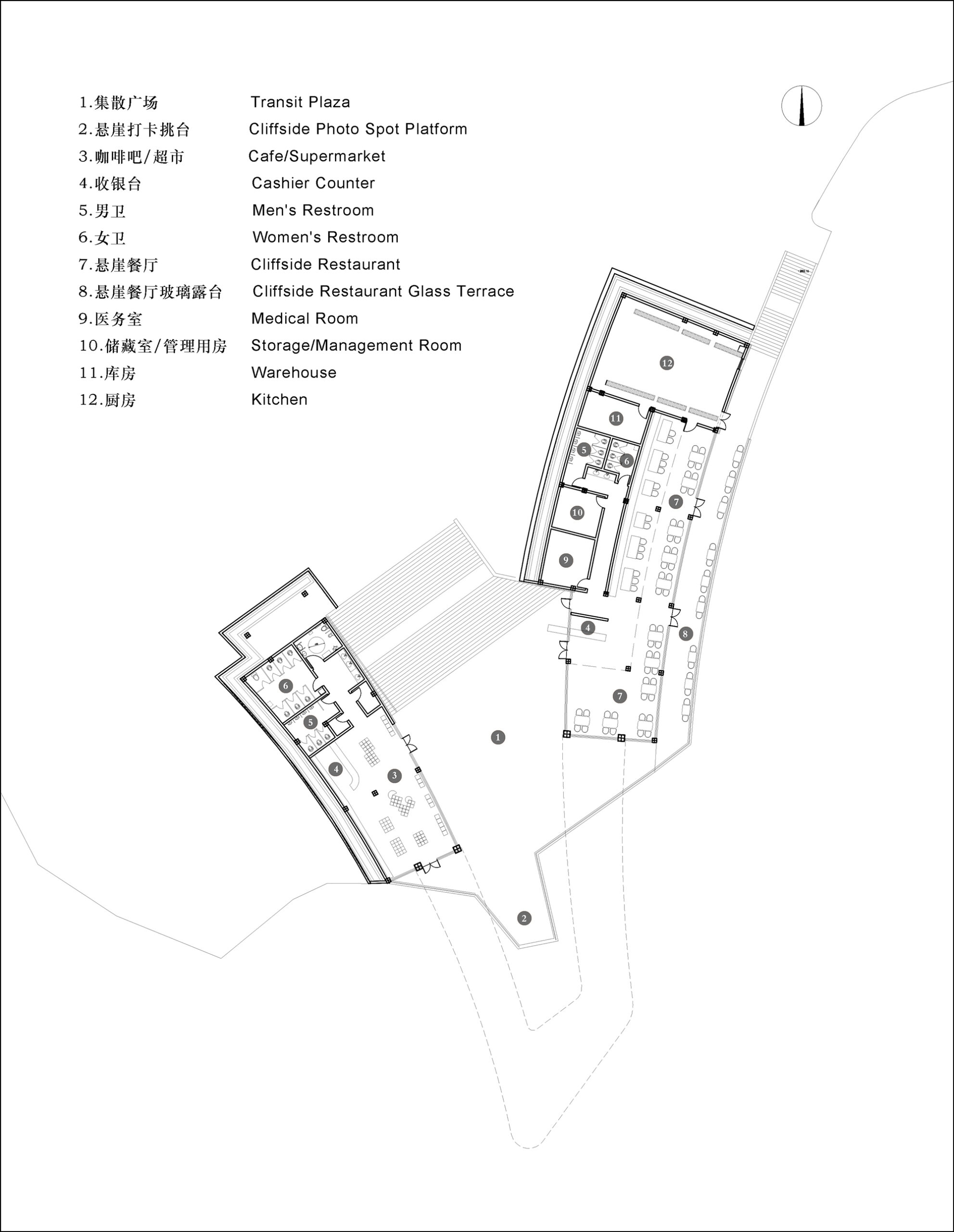

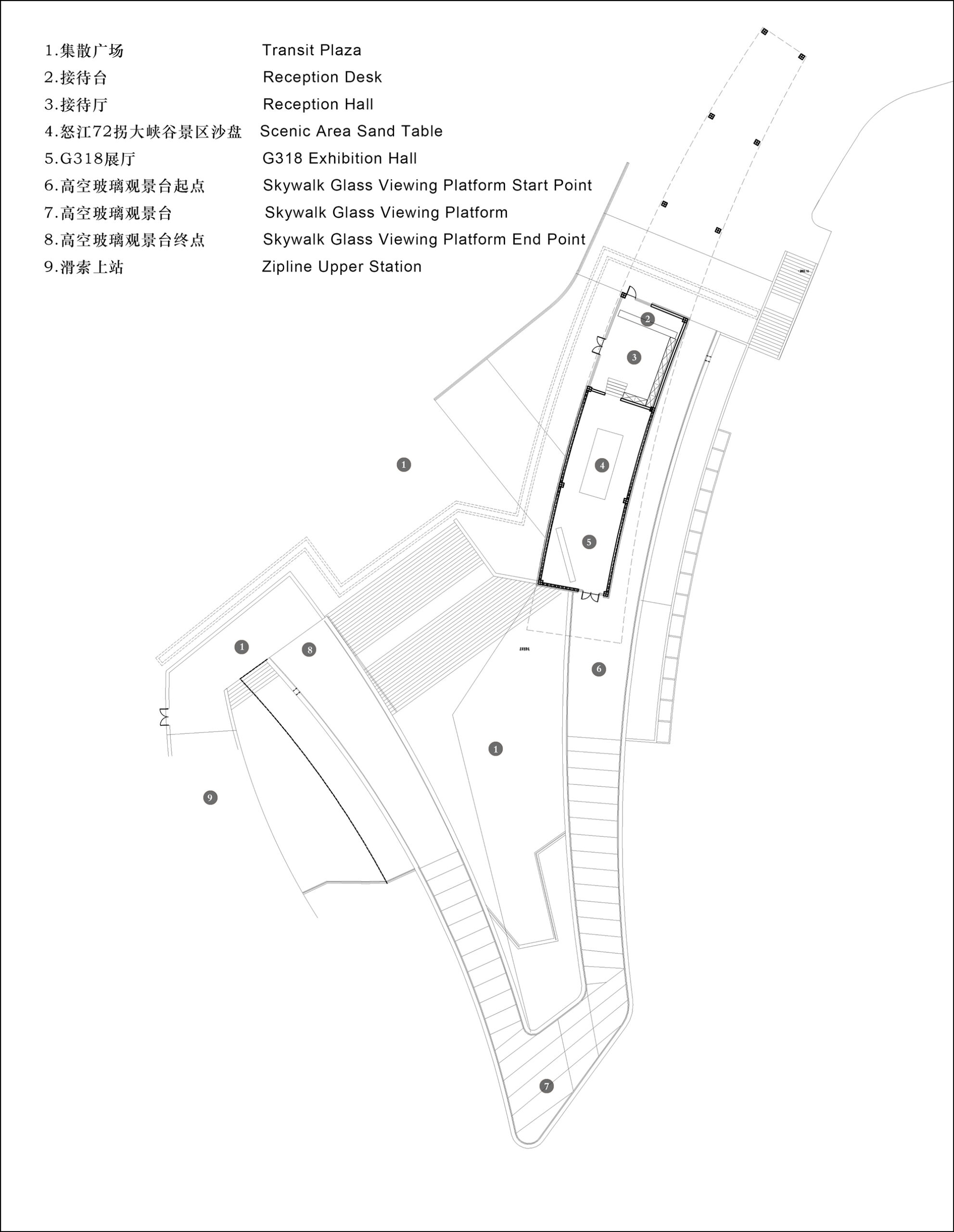

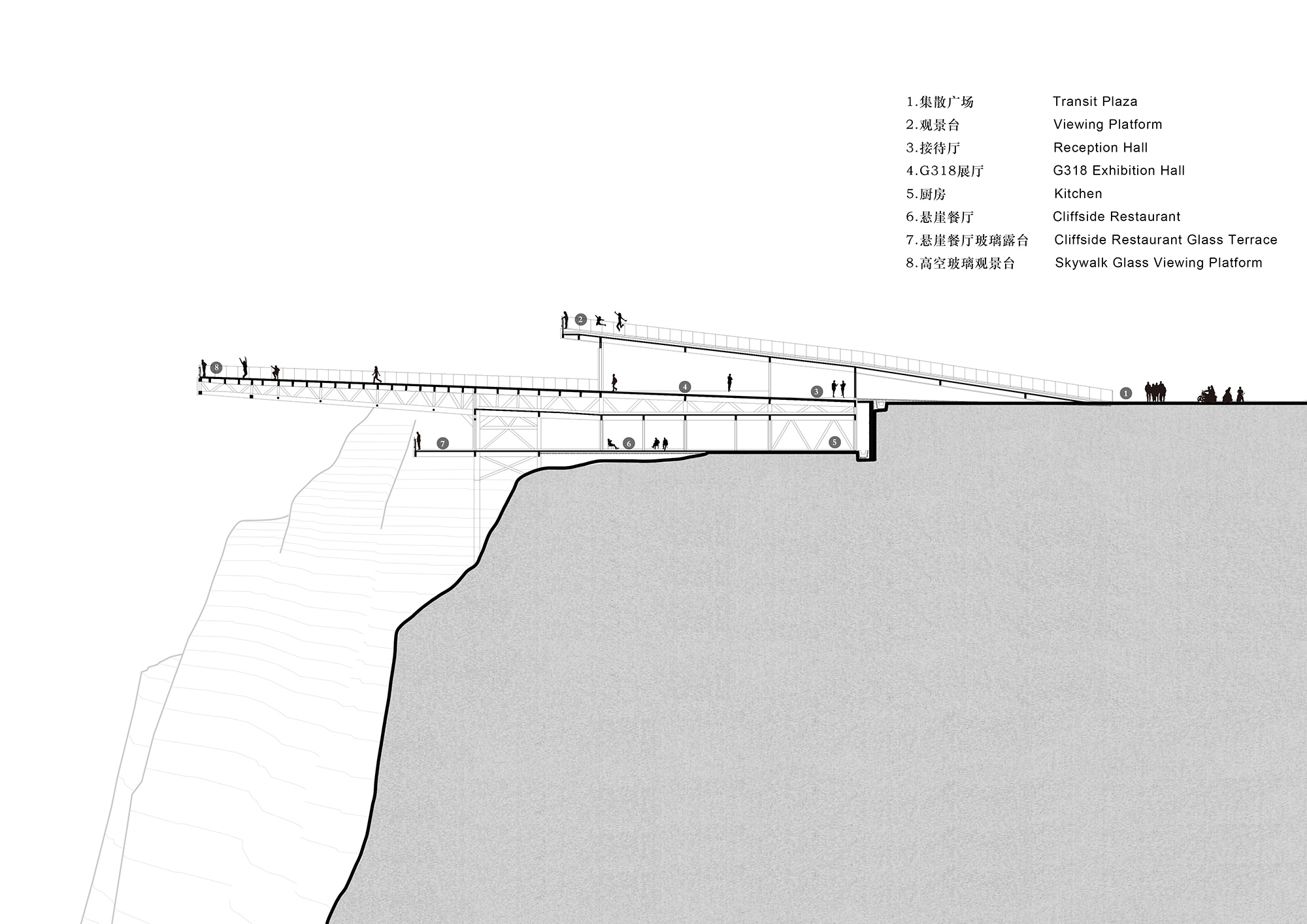

高所ガラス展望台の挑戦

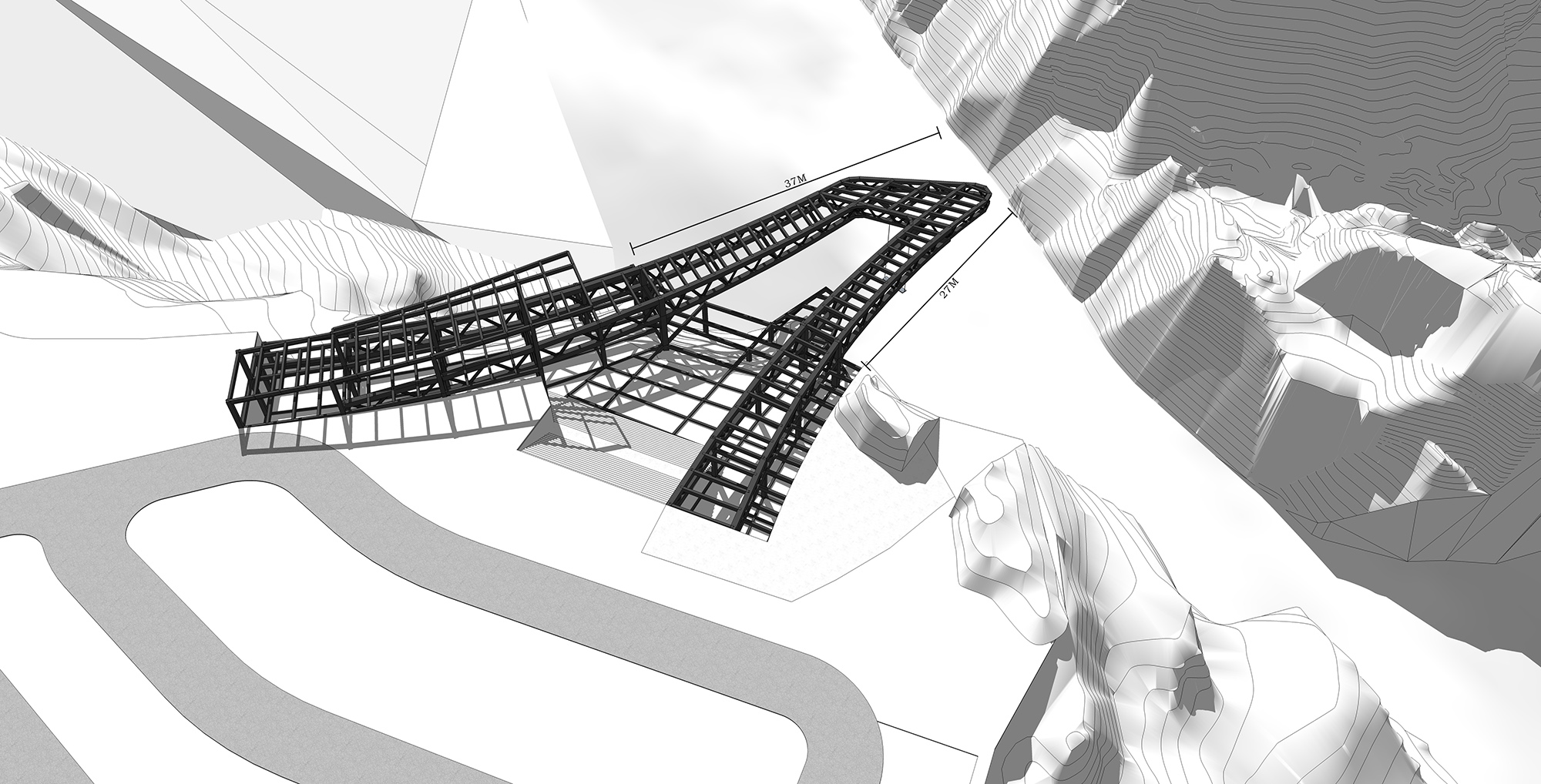

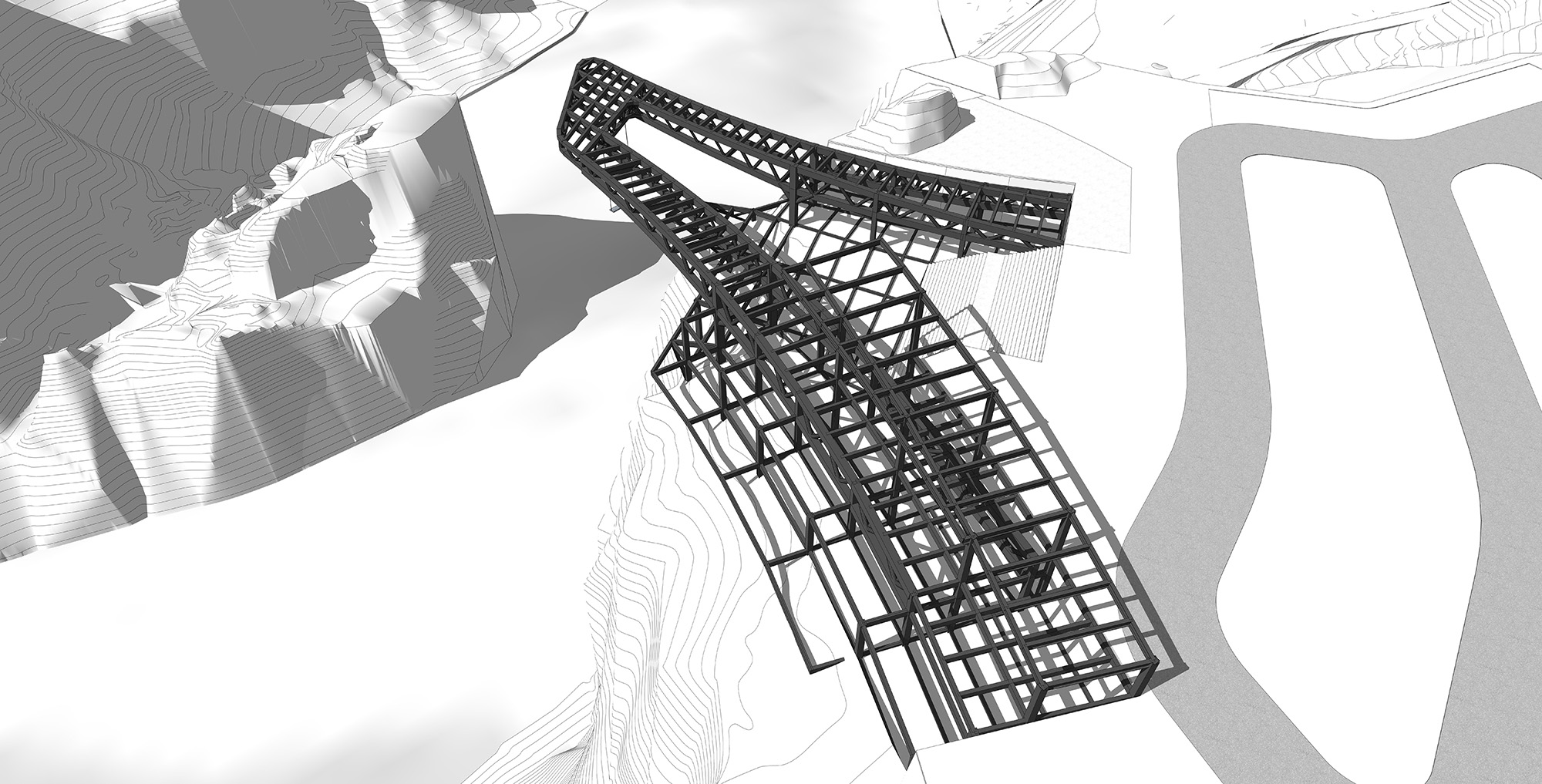

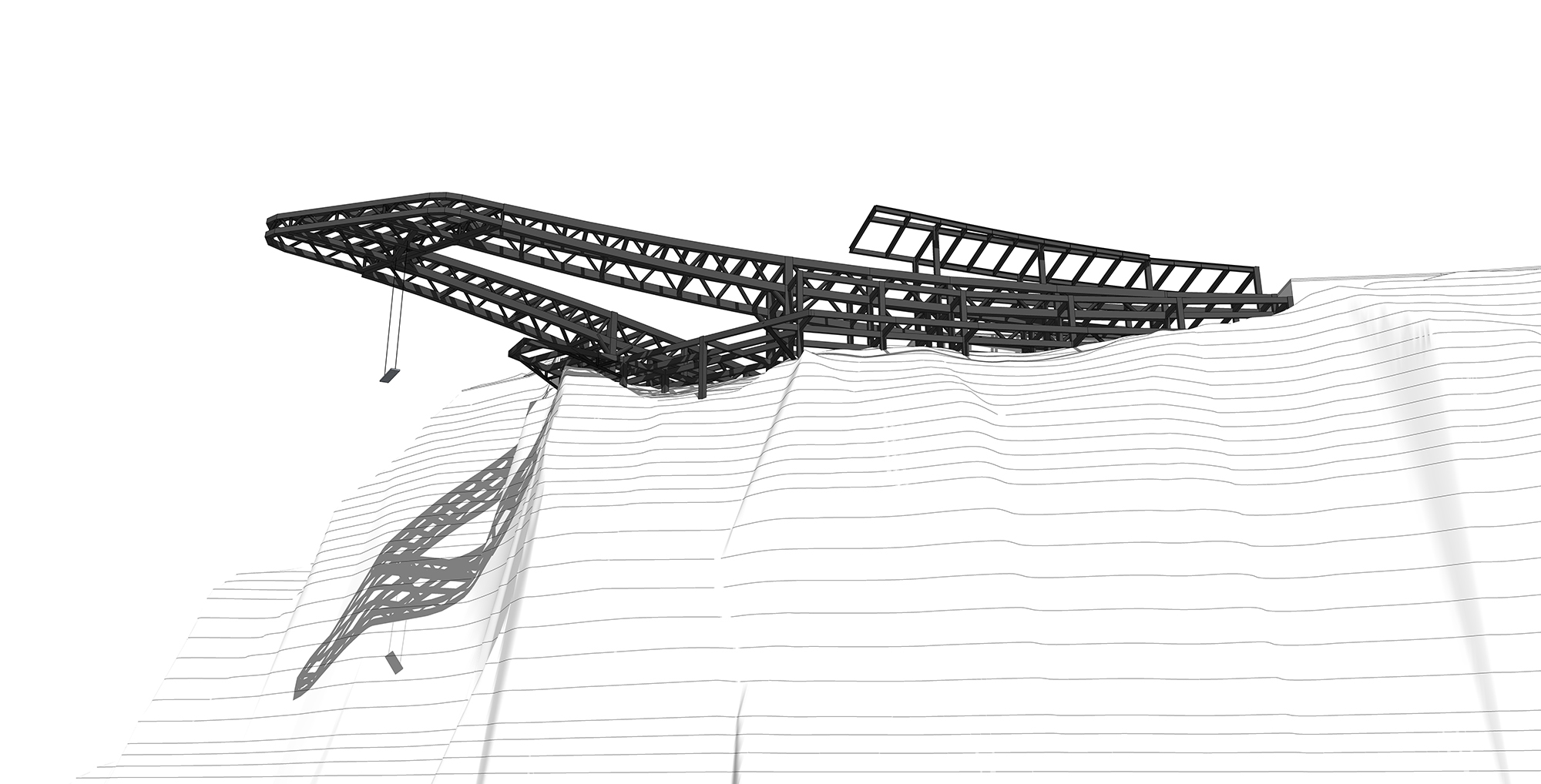

プロジェクトの中核をなす高所ガラス展望台は、ヘアピンカーブの道路形状に着想を得た。怒江峡谷の断崖に立ち、130m以上を見下ろす鋼製トラス構造が37m外側へ片持ちで突き出す。床面には高透明安全ガラスを敷き詰め、空中に浮かぶ「天路」を創出する。

© Arch-exist

© Chill Shine

怒江七十二道拐のスリリングなドライブ体験を究極の高所歩行体験へと昇華させ、訪問者が怒江峡谷の雄大な野生の美と息をのむ魅力を深く体感できるようにした。

外装材には主にチベットレッド色の耐候性鋼板を採用し、地域の色彩文化への呼応と周囲環境との差異化を両立させている。高耐候性鋼は頑丈で耐久性に優れるだけでなく、その粗い質感が周囲の荒々しい景観と対話と融合を繰り広げる。

© Chill Shine

© Chill Shine

かつての偉業を体感するジップラインとチャレンジブリッジ

怒江を跨ぐジップラインとスリリングステップ・チャレンジブリッジは、国内の類似アミューズメント施設では目新しい概念ではないが、ここに設置される必要性は極めて高い。

四川チベット公路の建設過程を振り返れば、同様のアミューズメント施設が数多く建設されていた光景が浮かぶ。まさにこうした極限の危険を伴う工法こそが、四川チベット公路という奇跡を可能にしたのである。

© Arch-exist

70年前、道路・橋梁建設技術が未熟だった時代に、建設者たちの知恵と勇気は実に称賛に値する。現代では高度な建設技術と手法を有するものの、怒江峡谷の地理的・交通的制約により、〈怒江七十二道拐展望台〉の建設では今なお数十年前からの「伝統的手法」に多く依存している。

ジップラインやチャレンジブリッジの体験を通じて、私たちは四川チベット公路建設の困難さをより深く理解する。これこそがそれらの存在意義であり、価値である。

© Arch-exist

スリリングな運転体験をもたらしてきた旧怒江大橋の物語

展望台からバソイへ向かう途中、わずか2km先に有名な怒江大橋が位置する。旧怒江大橋は鋼構造で、鋼板製の橋床は車両通行に耐える頑丈さを備えていたが、当時は厳重な警備が敷かれ、車両は検査のため停止し、一列に並んで渡らねばならなかった。

揺れる橋を渡る運転体験は、まさに心臓が飛び出そうになるほどであった。現在、新たな怒江大橋が完成し、旧大橋は歴史の尊き遺構となったが、その鮮烈な物語と光景は今も広く語り継がれている。

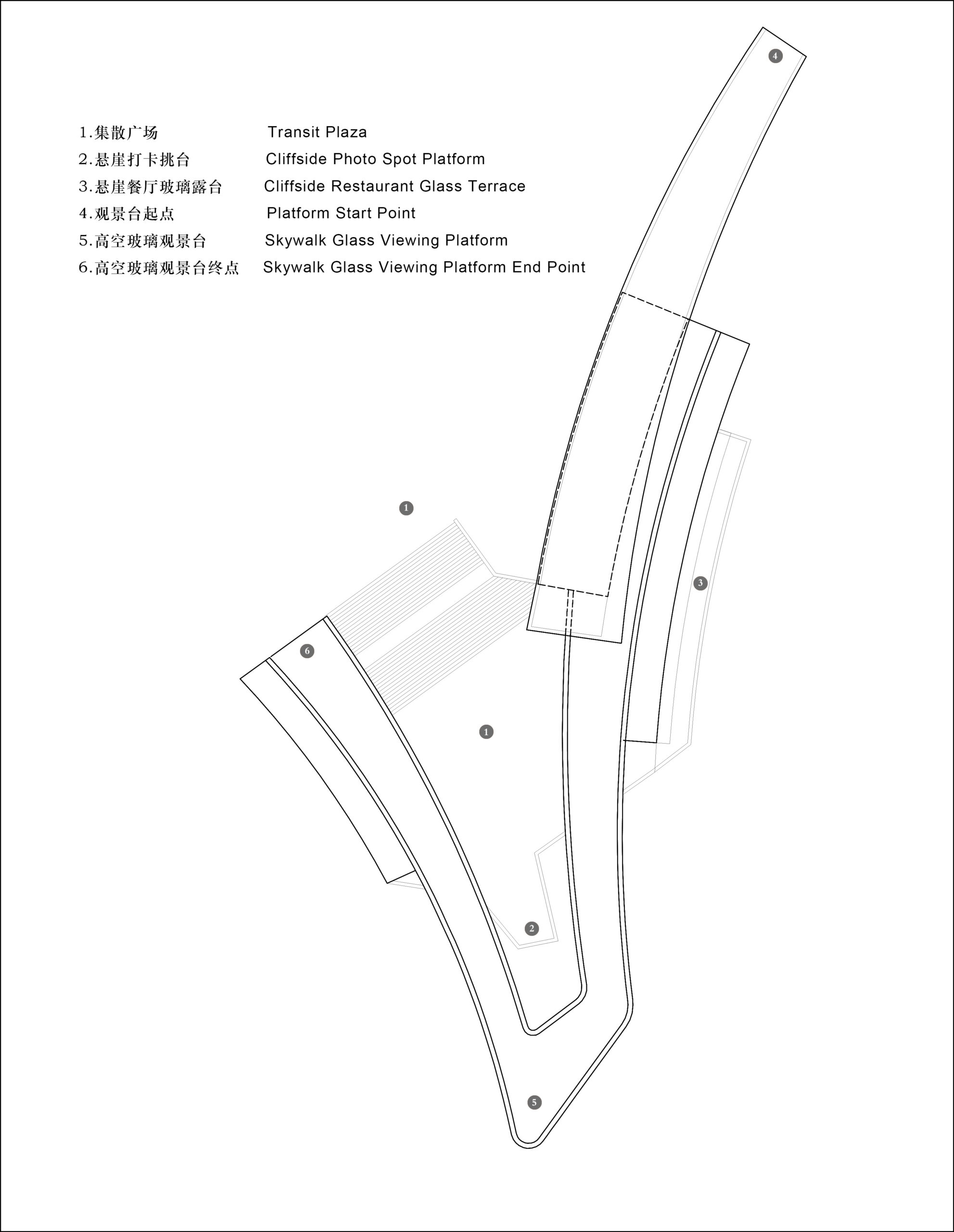

© Arch-exist

川を跨ぐガラス吊橋のデザインは、揺れる鋼鉄の旧怒江大橋に着想を得た。ケーブル橋の構造を採用したガラス吊橋は、揺れを自然に感じさせる。怒江の激しい風が不安定感をさらに増幅させ、高透明ガラス床が訪問者のアドレナリンを刺激する。同時にこのガラス吊り橋は怒江の両岸を結ぶ重要な連絡路として機能し、景勝地におけるハイキングやアウトドア活動などの将来の活動を大きく促進する。

怒江から50m上空に架かるガラス橋を歩く訪問者は、風を感じ、轟く川の流れと轟音を耳にし、砕ける波を間近に目撃する。これらの感覚は訪問者の心に長く残り、今後何年にもわたって記憶に波紋を広げ続けるだろう。

© Chill Shine

© Chill Shine

怒江南岸の観光用エレベーターは、急峻な地形が歩行を困難にするため設計された。利便性を考えれば、両岸にエレベーターを設置することも可能であった。

例えば北岸では、ガラス吊り橋を渡った後、エレベーターで楽に「葉見台」へ到達し、短い坂を上って「宇宙カプセル展望台」へ、さらに短い坂を上れば終了という、よりリラックスした快適な体験が可能であった。

Construction scenes similar to those of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway- plank road © Archermit

しかし私たちは、この快適さをあえて放棄し、北岸にエレベーターを設置せず、代わりに「天怒666階段」を建設した。息を切らしながらこの過酷な階段を登り終え、振り返って来た道を眺めた時、訪問者は四川チベット公路と〈怒江七十二道拐展望台〉の建設者たちが直面した困難を真に理解するだろう。

「自らの身体で険しい怒江を測る」という言葉の真意を、この時初めて深く理解できるのである。

© Chill Shine

© Arch-exist

旅の最終区間は確かに困難だが、重い荷物を背負うことなく自ら選んだ短時間の肉体疲労に過ぎない。しかしこれらの偉大な工学的偉業は、勇敢な魂たちによって成し遂げられたものであり、中には命を捧げた者もいた。

人生の成功は容易に得られるものではなく、往々にして成功に最も近い瞬間が最も厳しい。この最終区間は畏敬の念を抱かせるだけでなく、身体的な体験を通じて訪問者に体現的な理解をもたらすかもしれない。

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

〈怒江七十二道拐展望台〉の設計は、怒江の危険に直面する体験を極限まで高め、「危険の中の危険を求め、自らに挑戦する」というコンセプトを体現し、チベットに新たな地理的ランドマークを創出することを目指している。

G318を旅する人々が車という枠から解放され、自らの身体で怒江の危険を測ることができる。このエリアは、身体的・心理的・精神的な限界に挑戦する場を提供し、自らの忍耐力で測られる忘れられない旅の体験を創り出す。

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

© Arch-exist

© Chill Shine

© Chill Shine

© Chill Shine

© Chill Shine

© Arch-exist

General layout of the scenic area © Archermit

1F Plan of the high-altitude glass viewing platform © Archermit

2F Plan of the high-altitude glass viewing platform © Archermit

RF Plan of the high-altitude glass viewing platform © Archermit

Sectional view © Archermit

Steel structure model of viewing platform © Archermit

Steel structure model of viewing platform © Archermi

Steel structure model of viewing platform © Archermit

以下、Archermitのリリース(英文)です。

Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area , Tibet

Measure the Dangers of Nujiang with the Body—The Sichuan-Tibet Highway Warrior Challenge

Every child who dreams of Tibet holds a G318 dream. The Sichuan-Tibet Highway, renowned as “China’s Scenic Avenue,” has always been a sacred route for travelers. About 200 km past the junction of the southern and northern Sichuan-Tibet routes from Chengdu to Lhasa lies the most spectacular part of the journey. In the small town of Baxoi, meaning “village under the warrior’s mountain” in Tibetan, famous sights like the Bangda Grassland, Nujiang Grand Canyon, Ranwu Lake, and Laigu Glacier, all connected like sparkling pearls along G318. For those chasing their dreams on G318, the most anticipated thrill and challenge awaits in the “Devil’s Section” of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway within Baxoi—72 Turns of Nujiang River.

The saying ‘eyes in heaven, body in hell’ reflects the personal experience of many visitors to Tibet. Despite this, Tibet remains a spiritual destination for countless people. Whether it’s the cultural beliefs or the landscapes and local customs, the ‘experience’ is the key motive for all types of travelers to Tibet. Whether through prostration pilgrimage, trekking, cycling, or self-driving, self-challenge is the core belief and pursuit for many Tibet enthusiasts. In 2017, we introduced the famous eastern gem of Tibet, Ranwu Lake, through the Ranwu Lake International Self-Driving and RV Camping Project. Now, seven years later, we are excited to share the journey through the Devil’s Road, the 72 Turns of Nujiang. In March 2019, a bold and daring dream began to take shape on the cliffs by the river at the foot of the 72 Turns. After six years of tough challenges, in September 2024, the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area has been completed. Its arrival will offer G318 travelers a new playground to pursue thrills and challenges.

The Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area is located in Buze Village, Baxu County, Changdu City, Tibet, approximately 48.5 kilometers from Baxoi County and about 97 kilometers from Bangda Airport in Changdu. The scenic area is situated in the Nujiang Grand Canyon along the G318 Sichuan-Tibet South Line, in the region known for the most dangerous section of the G318, the famous ‘Heavenly Road 72 Turns’ and the Nujiang Grand Canyon. The design, construction, and future visitor experiences of the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area all embody a spirit of great challenge and pay tribute to the monumental achievements of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway. All design inspiration comes from this magical scenic avenue.

The high-altitude glass viewing platform serves as the core structure of the project, inspired by the iconic ‘hairpin turn’ road layout of the Nujiang River 72 Turns. Perched on the cliffs of the Nujiang Canyon, with a drop of over 130 meters, the steel truss structure extends outward with a single cantilever of 37 meters, forming the ‘hairpin turn.’ The ground is laid with high-transparency safety glass, creating a true ‘heavenly road’ in the air, transforming the thrilling driving experience of the Nujiang River 72 Turns into an ultimate high-altitude walking experience. This allows visitors to deeply experience the majestic wild beauty and breathtaking allure of the Nujiang Canyon. The exterior materials primarily consist of weather-resistant steel plates in a Tibetan red color, responding to the cultural significance of the region’s colors while also standing out from the surrounding environment. The highly weather-resistant steel is not only sturdy and durable, but its rough texture also engages in a dialogue and fusion with the rugged landscapes around it.

The zip line and Thrilling Steps challenge bridge that span the Nujiang River are not new concepts in similar amusement projects across the country, but their presence here is necessary. Looking back at the construction process of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway, one can find numerous scenes of similar amusement facilities under construction; it is precisely these extremely dangerous construction methods that have contributed to the miracle of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway. Seventy years ago, when road and bridge construction technology was still immature, the wisdom and courage of the builders were truly admirable. Although we now possess very advanced construction technologies and methods, the geographical and transportation constraints of the Nujiang Canyon mean that the construction of the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area still relies on many ‘traditional methods’ from decades ago. Through the experiences of the zip line and the Thrilling Steps challenge bridge, we can gain a deeper appreciation of the difficulties faced in building the Sichuan-Tibet Highway, which is the true significance and value of their existence.

Heading towards Baxoi from the scenic area, less than two kilometers away lies the famous Nujiang Bridge. The original Nujiang Bridge was a steel structure with a deck made of steel plates sturdy enough to support vehicle passage. Heavily guarded at the time, vehicles had to stop for inspection and queue up for single-file crossing. The experience of driving across the shaky bridge was nerve-wracking. Today, a new Nujiang Bridge has been completed, while the old Nujiang Bridge has become a revered piece of history, with its vivid stories and scenes still widely recounted and remembered. The design of the glass suspension bridge that spans the river was inspired by that shaky steel Nujiang Bridge. The glass suspension bridge adopts the form of a cable bridge, which naturally brings a swaying sensation. The fierce winds of the Nujiang River further intensify the instability, and the high-transparency glass deck adds to the adrenaline rush for visitors. At the same time, the glass suspension bridge serves as an important link between both sides of the Nujiang River, greatly facilitating future activities such as hiking and outdoor adventures in the scenic area. As visitors walk along the glass bridge, suspended 50 meters above the Nujiang River, they feel the wind, hear the rushing water, the roaring river, and witness the crashing waves—all so close. These sensations will linger long in the minds of the visitors, creating ripples in their memories for years to come.

The sightseeing elevator on the southern bank of the Nujiang River was designed because the steep terrain makes it difficult for tourists to walk. From a convenience standpoint, elevators could have been installed on both banks. On the north bank, for example, after crossing the glass suspension bridge, visitors could take an elevator to easily reach the Leaf Viewing Platform, ascend a short slope to the Space Capsule Viewing Platform, and then climb another short slope to finish, making the entire experience much more relaxed and comfortable. However, we chose to forgo this comfort and did not install an elevator on the north bank. Instead, we built the “Sky Fury 666 Ladder.” When visitors, breathless and letting out a string of curses, finally complete this challenging climb and look back at the road they’ve traveled, they will come to truly understand the hardships faced by the builders of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway and the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area. Only then can they fully appreciate the meaning of “measuring the treacherous Nujiang with one’s own body.” While the final stretch of the journey is difficult, it is still just a brief, voluntary physical exhaustion, unburdened by heavy loads. But achieving these monumental engineering feats was the work of brave souls, some of whom even gave their lives. How many successes in life are easily attained? Often, the moment closest to success is the hardest. This final stretch, beyond inspiring awe, may also allow visitors to gain an embodied understanding through their physical experience.

The design of the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area aims to elevate the experience of confronting the peril of the Nujiang River to the extreme, embodying the concept of “seeking danger within danger and challenging oneself,” thus creating a new geographical landmark for Tibet. It allows travelers on the G318 to break free from the confines of their vehicles and measure the peril of the Nujiang River with their own bodies. This area will provide visitors with a space to challenge their physical, psychological, and mental limits, crafting an unforgettable travel experience that is measured by their own endurance

Dreams grown on cliffs – the challenge of high-altitude engineering practice over six years

Tibet experiences over five months of snow and ice weather each year in most areas. The sudden rain, snow, high temperatures, and strong winds in summer create a very limited time frame and cycle for normal construction activities throughout the year. Additionally, Tibet’s complex terrain features rugged roads with many sharp turns and a high density of tunnels and culverts, making these challenges particularly prominent in sections like the Nujiang 72 Turns and the “Tiger Mouth” in the Nujiang Grand Canyon. Instances of landslides and mudflows causing road damage also occur frequently, significantly impacting the transportation of construction materials and equipment. Materials longer than 13 meters are nearly impossible to deliver to the construction site, and large construction equipment such as cranes and pile drivers cannot be transported. Road damage and harsh weather also contribute to uncontrollable transportation times. The high altitude presents a significant physical challenge for construction workers; for example, the Nujiang Viewing Platform is located at an altitude of around 2,800 meters, leading to six different waves of workers just for the pile foundation drilling work. Many workers from lower altitude areas simply cannot adapt to the high-altitude climate, which further limits the pool of available labor. High altitude also poses significant challenges for certain construction processes, such as electric welding, concrete pouring, and metal sheet installation. The temperature difference between day and night in Tibet is extreme, so careful selection of building materials is essential. It’s important to avoid using materials with a high deformation coefficient, as these can age, deform, or detach more easily due to temperature fluctuations. Suitable materials include stone, wood, cement products, locally sourced materials, and some metals with low deformation coefficients. Additionally, it is advisable to use adhesive construction techniques as much as possible and minimize the use of cement bonding methods. On one hand, the short construction cycle in cold regions is not conducive to cement bonding work, while significant temperature differences and winter freezing can lead to cracking, spalling, detachment, and alkali corrosion in cement joints.

The construction process of the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area faced a series of challenges that are highly representative of construction projects in Tibet, encompassing nearly all the issues encountered in the region’s architectural endeavors. From the very beginning of the project design, we established the concept of “challenge.” Beyond providing visitors with a unique “challenging” experience, the design and construction of the project itself represent a significant “challenge” in high-altitude engineering. This has great significance for our architectural practices in Tibet.

The north bank of the Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area is adjacent to the G318 highway, with well-developed road facilities, while the south bank only has rough paths for hand-climbing, making accessibility very poor. Additionally, the project is situated at a high altitude with low oxygen levels and is located right in the valley wind corridor, often experiencing winds of level six or higher. The geological structure of the mountain slopes on both banks is unstable, and rockfalls are common during the rainy season, posing significant safety hazards for construction. From the very beginning, starting with terrain mapping and geological surveys, the design work faced numerous challenges. To create the ultimate “extreme challenge” experience of the Sky Road 72 Turns and the Nujiang Grand Canyon, the design plans involved very bold attempts. Subsequently, extensive specialized design verification was conducted, including disaster assessments, wind tunnel tests, TMD calculations, and cantilever steel structure construction simulations, all providing sufficient technical support for the later construction phase. During the project’s construction, we collaborated with multiple authoritative institutions, industry experts, and professors, along with our construction team, to overcome numerous obstacles. After six years of hard work, the project was successfully brought to fruition. Here, I would like to highlight a few impressive moments that pay tribute to the wisdom and courage of our workers!

The scenic area’s buildings and structures are distributed across both banks of the Nujiang River, which spans over 260 meters. The south bank features rugged paths that require both hands and feet to navigate. Although detailed terrain mapping was conducted in advance, the actual measurement and alignment faced numerous difficulties. Some points were located on steep cliffs, and the strong winds in the valley made it impossible to control drones accurately; thus, we had to rely on RTK surveying equipment for manual alignment. Due to the lack of construction access roads, workers had to secure themselves with safety ropes and dangle over the cliffs to carry out measurements and alignment, a sight that was both alarming and concerning. But this was just the beginning of the story, merely a small overture.

The unique geographical location between the Sky Road 72 Turns and the “Tiger Mouth” of the Nujiang Grand Canyon made it impossible to transport large machinery to the site. During the construction of the pile foundations for the high-altitude glass viewing platform, 39 piles were distributed across different geological layers on the steep cliffs. Due to the lack of roads and a level working surface, we had to resort to manual water-cooled drilling methods for the pile foundation work. The substrate was entirely rocky, with constantly changing rock layers, and most of these layers were extremely hard. We tried over 50 different types of drill bits available in the domestic market, but none were able to reach the required drilling depth. The project team sent rock samples to tool manufacturers in Chongqing, Shandong, and elsewhere for analysis, which eventually led to the development of customized drill bits for the project. The deepest of the 39 piles reached 25 meters. Because of the depth, the later stages of drilling could only be conducted using a layered approach, drilling down 0.6 meters at a time. Workers used a 110 mm diameter water-cooled drill to create a circle of holes around the perimeter and then, secured by safety ropes, descended to the bottom of the 1.8-meter diameter hole to manually break up the remaining rock in the center, which was then hoisted out using a basket. This process involved drilling and extracting layer by layer, progressing downwards in increments of 0.6 meters. After changing six construction teams and with the effort of hundreds of workers over six months, the 39 pile foundations were finally completed.

The transportation of construction personnel and materials to the site was also a significant challenge. In the early stages of the project, due to the lack of access roads on the southern bank of the Nujiang River, construction workers had to drive several kilometers around to cross the river via a temporary bridge and then walk to the construction site. At an altitude of over 2,800 meters, it took workers nearly two hours to reach the site from the construction barracks, consuming about four hours for a round trip (without carrying any loads). The various building foundations on the south bank consisted of reinforced concrete deep piles, while the main structure utilized steel, concrete, steel components, weather-resistant steel plates, stainless steel, and special glass. Although the materials designated for the southern bank had undergone multiple design breakdowns, they were still quite heavy and could not be transported solely by manpower. Additionally, some small to medium-sized construction machinery (such as excavators, crushers, and air compressors) could not reach the south bank. To address these challenges, the project team implemented a temporary cableway similar to the one used decades ago during the construction of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway, allowing for the transportation of construction machinery and personnel between the two banks. Subsequently, a freight cableway was established to ensure that construction materials could be delivered smoothly to the southern bank. Through extensive coordination, a 100-ton crane was transported from the 72 Turns direction to the construction site on the northern bank, where a 60-ton tower crane was also erected. Once the construction materials arrived at the site, they were unloaded using the crane and transferred via the tower crane to a river-crossing hoisting platform. From there, the materials were sent across the river using the cableway, and subsequently, they had to be manually transported to various construction locations, requiring at least four transfer operations in total.

Due to the limitations of regional transportation, the seemingly simple task of pouring concrete became exceptionally challenging in the Nujiang area. The nearest concrete mixing station is located in Baxoi County, over 40 kilometers away, with a travel time of about one hour. However, due to the terrain and road conditions, the mixer trucks could not reach the southern bank of the Nujiang River, and their heavy loads also prevented them from using the freight cableway to cross the river. To address this issue, a steel cable bridge approximately 150 meters long was constructed over the Nujiang River, along with a dedicated concrete delivery pipeline laid on the bridge to transport the concrete to the opposite bank. However, the length of the pipeline often led to blockages during the concrete delivery process. If a blockage occurred, it had to be cleared within an hour; otherwise, the concrete would solidify, necessitating the installation of a new delivery pipeline. Moreover, the significant distance from the mixing station resulted in long transportation times for the mixer trucks, making the cross-river delivery quite complex. Therefore, each batch of concrete had to be delivered and poured with utmost urgency, requiring careful scheduling of the entire transportation and pouring process. Any delay, even minor, could result in a batch of concrete being wasted. The southern bank had multiple concrete pouring locations, and some points on the tops of cliffs had delivery distances that were too long for direct pouring using the concrete delivery pipes. In such cases, workers had to resort to self-mixing concrete, which significantly lowered the construction efficiency and caused the progress to be extremely slow in order to meet quality requirements.

In Tibet, where transportation is inconvenient and construction is greatly affected by weather conditions, steel structures are an ideal building method due to their minimal on-site construction volume, quick installation, and controllable overall costs. The high-altitude glass viewing platform features a steel truss structure, with the furthest cantilever extending 37 meters and the nearest one extending 27 meters. The truss height near the cantilever support is 2.4 meters, gradually decreasing to 1.5 meters at the cantilever end, which is more than 130 meters above the Nu River. Due to transportation restrictions on the G318, particular attention must be paid to the rational division of structural components when constructing with steel, ensuring that materials are split into transportable sizes while maintaining their mechanical performance. The entire steel truss was fabricated in 46 sections at the factory and then transported to the site for assembly and hoisting, with the main truss of the cantilever portion divided into 26 sections. The modular nature of steel structures facilitated the smooth transportation and installation of the viewing platform’s structural materials. The hoisting process requires extremely high precision in terms of pre-cambering the cantilever structure, welding, and controlling point displacement, compounded by the frequent strong winds on-site; this high requirement for labor skills is rare even in the Tibet region. The main exterior materials are made of red weathering steel plates and imported SGP laminated glass. These materials share the characteristics of excellent weather resistance, relatively simple construction processes, and ease of simplifying on-site operations, which is beneficial for project implementation. Other components of the project also utilize steel structures, weathering steel plates, and glass as primary materials, collectively creating a unique splash of red in the Nujiang Grand Canyon.

Many areas in Tibet rely on the tourism industry for development; without people’s participation, economic circulation would cease, leaving many places increasingly desolate and barren. In the early stages of the project, to support the tourism facilities in the scenic area, nearly 500 acres of fruit orchards were planned on the northern slope of the scenic area. Six years have passed in the blink of an eye, and this land, once a desert, is now covered in greenery. The fruit orchards have been in production for two years, and the ample sunlight in the region has resulted in exceptionally sweet and delicious grapes, pears, peaches, and apples. The Nujiang 72 Bends Grand Canyon scenic area has currently provided at least 48 jobs for locals, with an annual employment income exceeding 3 million yuan. In the future, we sincerely hope this project can empower regional tourism, attract more visitors, and inject new vitality into the development of this vibrant land. May this once-desolate cliffside bloom with countless hopes and make significant contributions to the tourism industry, economic development, job creation, cultural dissemination, and the export of local agricultural products in Tibet.

Project Name: Tibet: Nujiang River 72 Turns Canyon Scenic Area

Project Type: Architecture / Viewing Platform

Project Location: Tibet, Changdu City, Baxoi County

Creative Team: Archermit

Lead Architect: Youcai Pan

Design Director: Zhe Yang (Partner)

Technical Director: Ren Zhen Chen (Partner)

Design Team: Yu Zhao, Wenshuang Wang, Xiangxin Ge, Jincheng Guo, Xinyue Liu

Construction Drawing Design: Chengdu Sinayulian Architectural Design Co., Ltd.

Architecture Team: Mei Wang, Kan Wang, Ming Lei, Shankun Liao, Xupeng Ma, Xingqi Hao

Structural Team: Xiaobo Wang, Zhigang Deng, Xu Du, Pengze Qu, Tao Yang

Electrical Team: Zhongkai Mo, Yuliang Fu

Water Supply and Drainage Team: Genqiu Liu, Li Wu

Facade Team: Gang Li, Shiyao Song

Wind Resistance Test Research: Wind Engineering Test Research Center of Southwest Jiaotong University, Professor Haili Liao’s Team

Steel Structure Construction Process Simulation Analysis: Protective Structure Research Center of Southwest Jiaotong University, Professor Zhixiang Yu’s Team

TMD Damper Design and Construction: Chengdu Isolation Technology Co., Ltd.

Amusement Facilities Company: Xinxiang Mingyang Scenic Area Amusement Supplies Co., Ltd.

Project Owner: Baxoi County People’s Government, Baxoi County Eastern Tibet Source Venture Investment Co., Ltd.

Operating Unit: Tibet Asha Cultural Tourism Co., Ltd.

Photographers: Arch-exist, Chill Shine

Special Thanks (for Photography): Tsime Ciwang, Zha Xi Chengcuo, Zha Xi Ni Ma, Baima Lamu, Gaxi, Zha Xi Luobu,DanZeng Ciwang

Writers: Youcai Pan, Xiangxin Ge

Design Period: June 2018 – November 2018

Construction Period: March 2019 – September 2024

Land Area: Approximately 100 acres

Building Area: Approximately 800 m²

Construction Unit: Tibet Laigu Architectural Co., Ltd.

Construction Personnel (listed in order of participation, 329 people): He Jun, Zhu Zha, Liao Hengying, Yin Wenguang, Shen Lei, Zhou Shinen, Wu Chaojun, Wang Xingwen, Hu Xiaolin, Tang Yong, Zhang Zhongyi, Chen Mei, Yang Mingli, Kang Renqiang, Zhang Xiaotao, Zhong Qinglong, Liu Minghong, Liu Yu, Fan Junwen, Losong Ciren, Luo Zhong, Wang Jirong, Wang Yingdong, Yin Yuanjie, Star Ciren, Tang Yongbo, Liu Youlin, Xi Rao Tasi, Rong Wang, Ding Zeng, Ciren Wangdui, Zhou Congxing, Chen Guoyue, Liu Song, Zhou Congmu, Zhou Zhongfu, Xiao Yuanhua, Guo Zhenmao, Zeng Hua, Liu Jianming, Jiang Fajun, Zhou Jian, Fu Nenggang, Jia Liangzhi, Mao Shaozhong, Yang Jiajun, He Xuechun, Yin Yuanguai, Zeng Hua, Gong Qiu Zhan Dui, Yang Mingqi, Fu Xiaofan, Zhou Lixiang, Zhou Zengming, Zhou Huasong, Li Changming, Zhou Lieyong, Chen Yuanhua, Xie Cong, Yang Zhichen, Yin Huasong, Wang Yingcai, Xiang Ba, Losong Zaxi, Zhuoma Qunjio, Hu Xiaotao, Yang Yujian, Liu Fanyuan, Zhou Youping, Zeng Mingyuan, Zhang Jun, Luo Weicheng, Ma Fushuang, Chen Honggang, Daluo Qunpei, Ci Wang Zaxi, Chen Sida, Ma Yong, Li Jianhua, Hu Li, Luo Kaijun, Liu Guanghong, Yu Dajiang, Xiao Hua, Yang Jiajun, Luo Zejun, Zeng Mingju, Liu Xiaoyan, Qiu Kangrong, Wang Zhibiao, Dai Xinghua, Wang Yifei, Yang Jianhua, Yang Bing, Dai Xingjian, Ci Ren Qupei, Losong Zeren, Wang Yonggui, Liu Hongming, Huang Yong, Wan Zheng, Dong Guangfu, Tang Xingtong, Dong Guangzhao, Yang Wanhe, Duan Guowan, Duan Dingkang, Liu Kancang, Xu Jiajun, Duan Dinghong, Duan Dingfei, Qiu Congrong, Qiu Congan, Qiu Xuelang, Lü Changda, Dong Guiqiong, Ran Fei, Liu Bofeng, Hou Guanghua, Zhang Xuebin, Zhang Yingyou, Wang Zhonghua, Feng Bihua, Zhang Bo, Xie Wuge, Yang Wusan, An Xingxiang, An Wencai, Yang Muji, Yang Mingqi, Cao Xinzou, Huang Zhenpin, Mao Linli, Chen Qingchun, Huang Benxiang, Yan Jiali, Zheng Gang, An Tianhong, Xie Siji, Liu Yanxu, Liu Fanzhao, Wu Tianhui, Pang Xun, Zhou Jun, Yuan Jianbing, Zhou Jiafu, Zhou Ruhua, Luo Qiaoyou, Li Fazhun, Wu Xiujun, Hu Zhenglin, Luo Shangyou, Wu Shengtian, Zhou Yonghong, Chen Guoneng, Xu Xuebing, Duan Rongfei, Dong Guanghua, Zhou Youxuan, Shu Fan, Chen Yangquan, Hou Wenming, Yang Tongwei, Chen Sijun, Deng Zongmin, Zheng Mingyao, Hu Shouqi, Ye Yunxue, Fu Kaide, Zhang Guohong, Peng Zaixiang, Deng Qiao, Chen Huashun, Li Shengze, Yang Mingzhang, Li Jidong, Wang Jianchun, Fu Shanghong, Li Xianglong, Chen Xuelong, Mou Guo, Chen Xuelin, Jiang Rungen, Ye Ruixian, Chen Dianran, Gou Jinlong, Chen Yong, Liu Guangwei, Hu Zhaoquan, Liao Zhifu, Meng Xiaohui, Xiong Youliang, Peng Yongkai, Yang Guoyong, Zhou Anlin, Wang Chaoyong, Xie Guangcai, Xie Guangwu, Liu Dexun, Deshi Baizong, Chen Guoshun, Wu Jiaqiang, Lin Yuantai, Losong Dawai, Bangbang Zhuzhu, Losong Rinqing, Losang Tujian, Losang Yangzong, Da Ci, Ming Zhu, Ding Zeng Quping, Silang Luozhu, Duoji Ciren, Basang Dawa, Duntu Qunpei, Luozhu Jiangcun, Losong Zhuoma, A Wang Qunpei, Losong Qunpei, Zhuoma Yongzong, Losang Nazhu, Suolang Cuomu, Losong Kezhu, Ding Zeng Quzhen, Hu Jianfeng, Losong Zexi, Bu Qiong, A Wang Luobu, A Wang Jia Cuo, Losong Zhuoga, Ang Wang Cilie, Cangxi Puci, Deng Zhu Renqing, Zequ Luobu, Luobu Wangxiu, Yang Tianjin, Zhou Ping, Cheng Julian, Wang Xilang, He Mingyou, Yu Chuan, Zha Xi Ni Ma, Xia Dong, Li Dahai, Yang Yong, Jiang Zhao Li, Deng Yunhua, Deng Hua, Deng Xiaobo, Deng Bangwen, Deng Yusong, Jin Xing, Jin Chongsheng, Jin Chongjian, Wu Hongcai, Gao Shimao, Huang Yong, Huang Gang, Yang Zhiru, Wang Chaorun, Han Meijiao, Jiang Zhirong, Zheng Yuwei, Jiariz, Peng Xiaocheng, Zhang Shisan, Huang Shuai Shuai, Lin Xin, Xu Fuhong, Zhang Zhaolin, Li Changwen, Shang Shucheng, Lei Pengyou, Li Yong, Xi Da Bo, Du Xianxing, Zheng Fei, Li Dashan, Li Xin, Liu Qinqin, Wang Decai, Guo Wen, Han Dechang, Li Dongsheng, Peng Yang, Gou Chengxun, Huo Dongwu.

Building Materials: Steel Structure (Fluorocarbon Paint),Patterned Steel Plate,Weathering Steel Plate (Tibetan Red),Galvanized Rectangular Steel Pipe,Stainless Steel Profile,SGP Laminated Ultra-Clear Glass (Flooring),Laminated Ultra-Clear Glass (Railing Panel),Insulated Ultra-Clear Glass (Curtain Wall),Stone,Local Rough Stone,Veneer Panel,Coating (Multi-Color),Ceramic Tile

Archermit 公式サイト

http://www.archermit.com